Building Laundro-Metric

Documentation of my project learning embedded C++ and hardware design by building a washing machine monitor.

A few weeks ago I found myself in my apartment building's hobby room, hunched over a soldering station, trying not to destroy another MPU6050.

The idea was simple: build something that detects when our washing machine is running, monitor the wash cycle, and sends a notification when it finishes. The result is Laundro-Metric, and you can see it live at laundro.borjessons.deno.net.

The Hardware

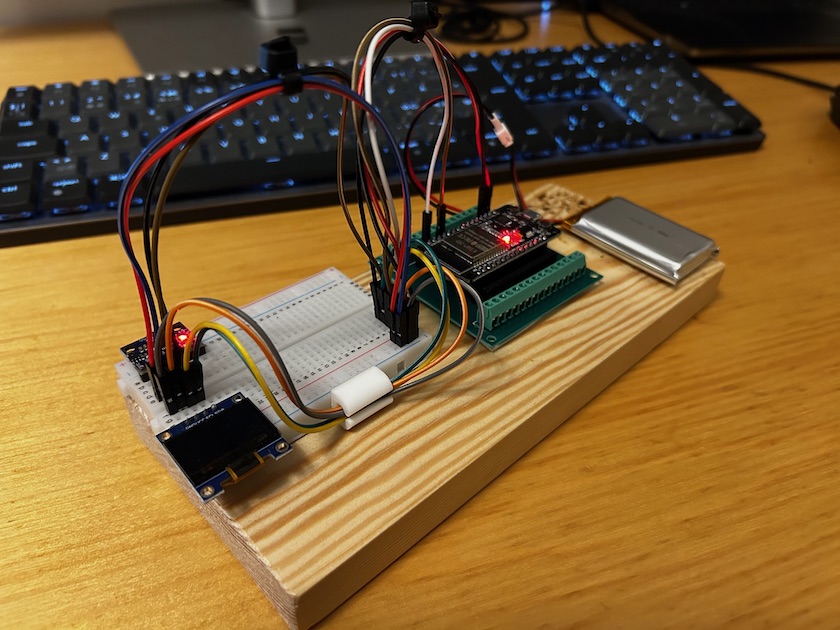

The core is an ESP32 paired with an MPU6050 accelerometer. Measure vibrations. If it shakes, it's washing. If it stops, the laundry is done.

I glued the ESP32 to a wooden plank (high-tech chassis), added a 2000 mAh LiPo battery via a JST-PH connector, and wired up a TP4056 for USB-C charging. The whole thing is taped to my washing machine with double-sided tape. It works.

The Soldering Problem

If you've never soldered before: the iron matters.

My first one was a cheap stick that couldn't maintain temperature. I didn't know that at the time, so I assumed I was just bad at it. After burning and destroying my first MPU6050 trying to attach header pins, I did some research and bought a Stannol iron. Night and day difference.

I also found a hobby room in our building with proper lighting and a fixture to hold the board steady. Turns out, soldering isn't that hard when you're not fighting your equipment.

The Backend and Frontend

The hardware sends data to a server I built with Deno and Fresh 2.0, hosted on Deno Deploy.

Deploying to Deno Deploy is almost stupidly simple—push to GitHub, done. The backend uses Deno KV for persistence, which means no database setup, no connection strings, just a key-value store that works out of the box.

When the ESP32 detects a state change (idle → washing → spinning → finished), it sends a POST request. Communication is protected with a simple API key. The frontend show the status in real time with Server-Sent Events (SSE). When a cycle finishes, the recorded data is summarized and stored in a separate KV collection, which feeds a history page with graphs showing past wash cycles.

There's also an /admin page with CRUD operations for managing the raw data in

the KV store, plus the last heartbeat timestamp for debugging.

Discord Notifications

One thing I added early on was a Discord webhook. When the washing machine starts or finishes a cycle, it sends a notification to our family Discord server.

Power Management

To save battery, the device spends most of its time in Deep Sleep, waking up every 60 seconds to take a quick, low-power vibration reading. If it detects movement, it runs a quick 'debounce' check to rule out false alarms (like someone just bumping the machine). Once a real wash cycle is confirmed, it shifts into an active mode, waking up more often to run detailed calculations and track exactly when the cycle starts, spins, and finishes.

But if the machine sits idle for days, how do I know the device is still alive? I added a Heartbeat—every hour, it wakes up briefly to ping the server. If the server doesn't hear from it for over an hour, it flags the device as offline.

Writing all this in C++ was new territory for me, my day job is Java. But it turned out to be pretty manageable with an LLM as a pair programming partner. Actually kind of fun.

The Calibration Problem

The tricky part was sensitivity.

The first 30 minutes of a wash cycle involve very gentle tumbling. The accelerometer picks up tiny movements, but they're buried in noise. My initial approach was to set a threshold for the RMS (root mean square) of the acceleration, but the baseline reading was inconsistent. Sometimes it read 9.81 m/s², sometimes 9.78, sometimes 9.85. That noise made it impossible to set a low threshold.

The fix was to calibrate the sensor at rest and compute a stable baseline. If I can reliably measure "zero" when the machine is off, then any deviation—no matter how small—is a signal. This let me drop the RMS threshold to almost nothing, making the system sensitive enough to catch even the subtlest vibrations at the start of a cycle.

I used Welford's online algorithm to compute mean and variance incrementally. The calibration runs until the standard deviation drops below a threshold, meaning the sensor has stabilized. Then I use a trimmed mean to reject any outliers. The below code snippet is redacted for brevity, but explains the gist of it.

std::vector<float> samples;

samples.reserve(Config::Calibration::MAX_SAMPLES);

while (n < MAX_SAMPLES) {

float mag = calculateMagnitude(mpu.getEvent());

samples.push_back(mag);

n++;

// Welford's online algorithm for mean and variance

float delta = mag - runningMean;

runningMean += delta / n;

runningM2 += delta * (mag - runningMean);

// Check for stability convergence

float stdDev = sqrt(runningM2 / n);

if (n >= MIN_SAMPLES && stdDev < STABILITY_THRESHOLD) {

// Trimmed mean rejects outliers for final baseline

std::sort(samples.begin(), samples.end());

return calculateTrimmedMean(samples);

}

}What I Learned

- Bad tools waste your time. If something feels harder than it should, check your equipment before blaming yourself.

- Microcontrollers are just fun. There's something deeply satisfying about working with real hardware. The I/O possibilities are endless: sensors, motors, LEDs, speakers. After years of pure software, building something physical that actually does something in the real world is refreshing.

- Deno Deploy is great for small projects. No config, no infra, just push and it runs.

- Fresh 2.0 is a joy to work with. Minimal boilerplate, islands for dynamism (javascript hydration), file-based routing, partials -> perfect for a project like this.

- IoT devices need a heartbeat. Silence doesn't mean everything is fine, it might mean the battery is dead.

- Deno KV. No need for a database, just a key-value store that works out of the box.

— Robin